Since time immemorial, our people have recognized and revered the sun's power. Powering our lives with solar offers a way to live in alignment with our values, bring electricity to homes in off-grid areas, advance sustainable economic development, and build energy resiliency and sovereignty to protect our people from rising electricity prices and blackouts. However, access to solar energy technology is often confusing, burdensome, and expensive. Community solar programs address these challenges.

Community Solar

What is Community Solar?

Community solar is an affordable way for Tribal community members to go solar without having to pay for individual rooftop installations. Through the passage of the Community Solar Act in 2021, New Mexicans can benefit from community solar programs.

Sign Up for Community Solar

Do you want to lower your energy bills and support clean, renewable, and reliable energy? Become a community solar subscriber!

How does it work?

There’s no cost to join, no need to install anything, and no risk of paying more than your usual utility charges.

Why sign up?

By signing up, renters, homeowners, and business owners can reduce their energy bills by 10-28%.

Who can sign up?

Customers of PNM, El Paso Electric (EPE), and Xcel (SPS) in New Mexico are eligible to sign up for community solar. Whether you rent or own your home, you’re eligible. Even if you live in an apartment or can't install rooftop solar, this program was designed with access in mind - especially for those who’ve been left out of clean energy options in the past.

How do I sign up?

You can sign up quickly and easily on Solstice’s website. It will only take a few minutes!

Resources

Questions to Ask Community Solar Developers

Why Community Solar?

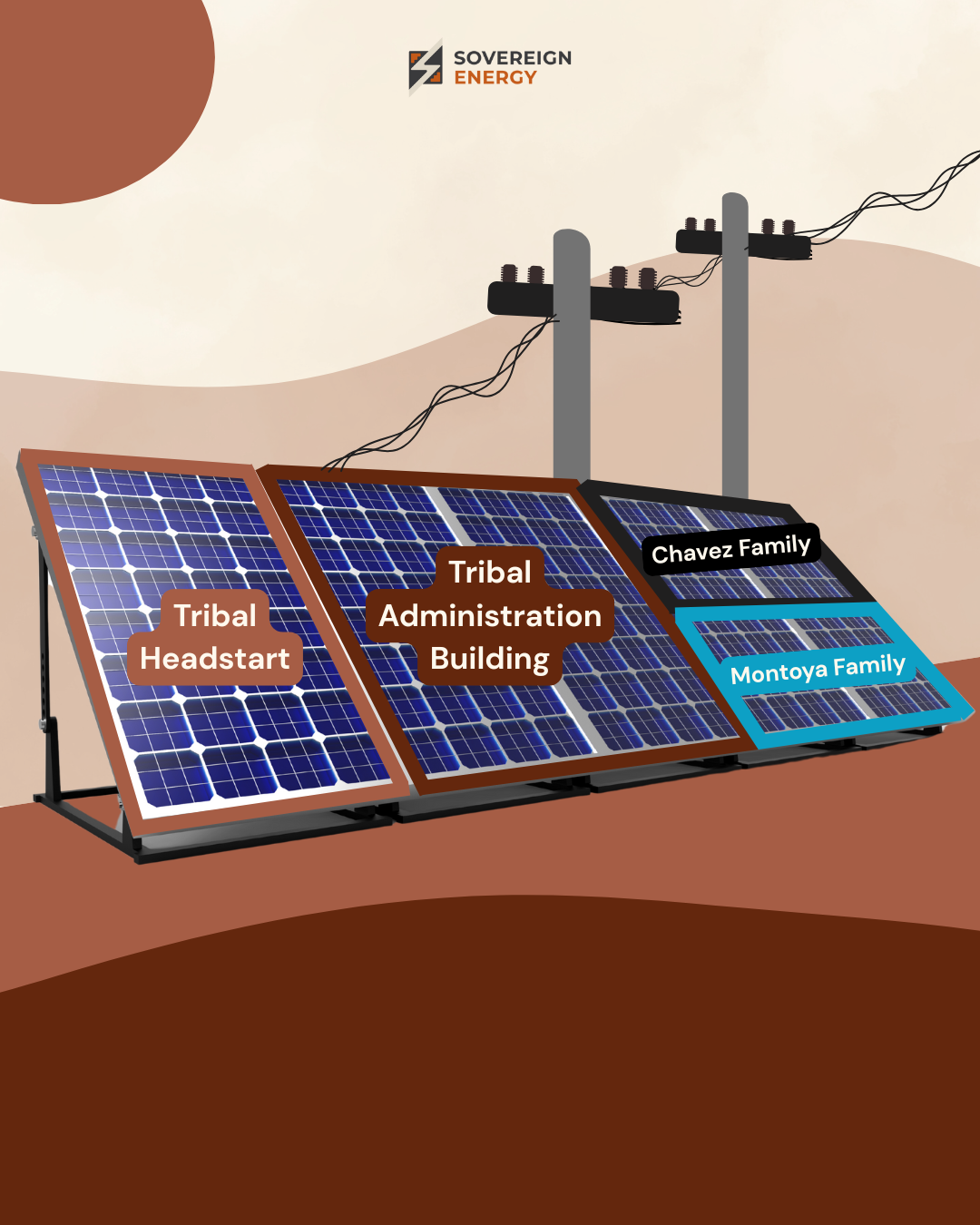

Families and individuals can join a community solar program by subscribing to a community solar facility, providing them virtual access to a shared solar array within or near a community. Participants of a community solar array are often called “subscribers,” and a single community solar array can provide power for a mix of different subscribers, depending on the size of the solar array. One project could provide power to a Tribal administration building, education center, health clinic, casino, and individual households. Tribal members can subscribe to facilities anywhere within PNM's service territory, meaning the array may or may not be located on Tribal lands. This means that if your Tribe does not have a community solar array, you can still participate in the program if you are a PNM customer.

Frequently Asked Questions

Tribal Community Solar Development

-

A community solar project is essentially a shared solar energy project that benefits multiple participants in a local area and is an affordable way for Tribal communities, renters and homeowners, local businesses, farmers, schools, and others to have access to solar energy.

Participants of a community solar array are often called “subscribers,” and a single community solar array can provide power for a mix of different subscribers. One project could provide power to a Tribal administration building, education center, health clinic, casino, and individual households. The solar panels are usually located in a central area, rather than on individual homes or buildings. This could be a community garden, a field, or even a rooftop of a suitable structure.

Through this program, subscribers can expect 10-20% in savings on their utility bills. Those who join a community solar program by subscribing to the facility have access to the electricity created by a shared solar array within or near a community, offering access to clean energy without individual solar installations on each building.

Tribal community solar offers Tribes the potential for self-sufficiency, community development, and alignment with Tribal values.

Community Solar Act

-

Community solar programs are typically enabled through state policy. A total of 24 states have statewide programs through legislation, and in 2021, the New Mexico Community Solar Act created the policy foundation to support community solar in New Mexico. The Act has unique provisions for “Native community solar projects” in recognition of the sovereign status of Tribal Nations. Projects off Tribal land are subject to the restrictions outlined in the state program, but projects on Tribal land remain exempt from state limitations. New Mexico is the only state having these unique Tribal exemptions.

As defined by the Community Solar Act, a "native community solar project" is “a community solar facility that is sited in New Mexico on the land of an Indian nation, tribe or pueblo and that is owned or operated by a subscriber organization that is an Indian nation, tribe or pueblo or a tribal entity or in partnership with a third-party entity.”

-

Community solar projects on Tribal land and off Tribal land share the core concept of shared access and benefits of a solar project, but there can be some key differences.

Link to the differences here.

-

Community-scale projects allow for the following:

Advancing Tribal energy sovereignty

Savings on electricity bills

Profit generation

Reduce carbon emissions and reliance on fossil fuels

Diversify energy supply with local and renewable sources

Job development (construction and maintenance)

Improve the reliability and resiliency of the energy grid

-

Tribes are sovereign nations and are not under the jurisdiction of state or local authorities. However, many Tribes rely on electric utilities that fall under state oversight, adhering to state-directed policies and regulations. Until the inception of the Community Solar Act, Tribes could only embark on community solar projects with support from their utility providers.

With the enactment of the Community Solar Act, net-metering regulations were introduced, establishing a framework for utilities, consumers, and businesses to operate under. This framework ensures stable financial conditions for evaluating the economic viability of projects. Net metering involves a billing mechanism that credits utility customers for surplus electricity they generate and export to the grid.

The Community Solar Act mandates the participation of investor-owned utilities (IOUs) such as PNM, Xcel Energy, and El Paso Electric in the community solar program. The rulemaking process for community solar was overseen by the New Mexico Public Regulation Commission, requiring each utility to submit their proposed energy valuation for approval. These rates are now monitored by the NMPRC to ensure that utilities accurately assess the value of the energy produced.

-

Rural co-ops may opt-in to the community program, but they are not required to support community solar projects because they are not state-regulated in the same way as other investor-owned utilities. Rather, the co-op regulatory board is responsible for rule-making to self-regulate the co-op. When a co-op utility is not state-regulated, the Tribe may have little ability to participate in or influence decision processes and co-op planning without going to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission.

Rural distribution co-ops do not own any generation assets but instead buy power from other “generation and transmission” providers. Most rural distribution cooperatives in New Mexico are members of Tri-State Generation & Transmission, Inc. The contractual relationship with Tri-State limits the amount of self-generation an individual co-op can do, and each co-op member can only generate up to 5% of their own electricity needs.

There are a few possibilities for your Tribe to pursue a community solar project even if your rural cooperative hasn't opted into a formal program. Check with your rural electric cooperative about their policies on self-generation and if there is a possibility to develop more generation to serve the distribution network. This might allow your Tribe to install a smaller community solar project to offset some electricity usage. In addition to negotiating directly with the co-op board, Tribes can connect with experts at the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association (NRECA) for additional support.

While rural electric co-ops may not be subject to state regulation, they are under the jurisdiction of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, and Tribes can appeal to FERC on issues relevant to Tribal solar deployment. Tribes can also negotiate using their rights of way for access to their lands.

In the long run, the Tribe can explore additional strategies to encourage the cooperative to participate in the community solar program. One approach could involve Tribal members running for election to serve on the cooperative's board of directors. This would provide an opportunity to directly influence decision-making within the cooperative and advocate for the adoption of community solar initiatives.

-

Step 1: Strategy & Goal-Setting

Identify Tribe’s goals for solar development. This may happen through discussions with Tribal leadership, community members, and other involved stakeholders

Have initial discussions with its utility to determine if there are any policies or regulations that may prevent the feasibility of solar projects

Gather all relevant data and understand Tribal role options to make a first pass at a potential project in line with the Tribe’s strategic economic, energy, and climate goals

Step 2: Planning & Pre-Development

Determine the Tribe’s desired role in the project, which can range from acting as the owner/operator of a facility or leasing the land to a third-party developer

Reach out to the respective utility to determine project and siting viability

Explore project scenarios and estimated values

Consider adopting a Tribal resolution outlining the Tribe’s support of community solar to be used shall a grant opportunity arise or in the event of governance turnover

Vet community solar companies and select a business partner(s)

Outline permitting and siting process

Begin to identify which subscribers the project is intended to serve

Step 3: Development & Business Arrangements

Finalize economic assumptions and Tribal roles

Determine financial partnerships and ownership structure

Finalize project siting and permitting

Submit interconnection application to the utility interconnection

Finalize offtake agreements (if applicable)

Identify workforce development goals

Step 4: Construction

Begin project construction

Implement workforce development goals

Begin signing up subscribers

Step 5: Operations & Maintenance

Project is interconnected to the grid and begins operating

Maintenance plan implementation

-

A Tribe may pursue multiple types of solar projects depending on their goals. Some factors that a Tribe may consider in assessing which type of project to pursue include:

Goals of the project

Project cost and economics

Land availability

Federal incentives

Jurisdiction and utility regulations, including net metering and interconnection rules

Available infrastructure (transmission, distribution lines, substations, feeders)

Community Solar Project Ownership & Project Finance

-

Third-party financing and ownership of community solar is typically structured through a lease or power purchase agreement (PPA). A community solar developer will install a solar array with little to no upfront cost for the Tribe.

In a lease, the community solar developer leases the land from the Tribe and maintains ownership of the system.

With a PPA, the customer pays a set rate for the electricity generated by the community solar array.

For Tribes seeking to avoid upfront expenses, third-party ownership and financing can be appealing. With third-party ownership, the owner and operator of the project bears the project and financial risk. The company also manages system upkeep, which is an essential consideration if a Tribe is short staffed or does not have the capacity to manage the system on their own.

Project financing is extremely complex, and each solar developer has their own internal financial models. It's advisable for Tribes considering third-party ownership to evaluate proposals from multiple community solar developers to identify the most advantageous arrangement.

While many solar companies prefer sole ownership and operation of projects, partnership flips or ownership transfers may occur, transferring ownership from the third party to the Tribe in certain cases.

Sovereign Energy has compiled a list of "Questions to Ask Community Solar Companies" to provide additional assistance to Tribes in navigating discussions or evaluating project proposals.

Participants of a community solar array are often called “subscribers,” and a single community solar array can provide power for a mix of different subscribers. One project could provide power to a Tribal administration building, education center, health clinic, casino, and individual households. The solar panels are usually located in a central area, rather than on individual homes or buildings. This could be a community garden, a field, or even a rooftop of a suitable structure.

Through this program, subscribers can expect 10-20% in savings on their utility bills. Those who join a community solar program by subscribing to the facility have access to the electricity created by a shared solar array within or near a community, offering access to clean energy without individual solar installations on each building.

Tribal community solar offers Tribes the potential for self-sufficiency, community development, and alignment with Tribal values.

-

Many Indigenous communities view project ownership as pivotal in advancing Tribal sovereignty. However, each Tribe maintains its distinct perspective on Tribal energy sovereignty, with the determination to pursue project ownership ultimately lying within the Tribe's discretion. Numerous factors influence the assessment of whether project ownership aligns with a Tribe's objectives. Ownership entails increased responsibility and risk for the Tribe, necessitating consideration of factors such as risk tolerance, economic objectives, internal staffing capacity, asset protection, and long-term project management. With the availability of new federal tax incentives and grant funding, owning community solar arrays has become more economically feasible for Tribes.

-

It's important to understand that the ROI (Return on Investment) for a community solar array can vary depending on several factors.

The average ROI for a solar farm often falls somewhere between 10% and 20%, and we can speculate that community solar would provide the same ROI. While community solar projects function differently than traditional solar farms, both involve generating solar energy. This suggests similar potential returns, though it's important to consider factors that might affect community solar specifically.

Key factors affecting ROI: Location (sunlight hours), electricity prices, project size, system efficiency, and available incentives all play a role.

Here's why the range exists:

Different companies have different ROIs that must be met to draw their interest to a project. Tribes also have their own ROIs that must be met to fulfill the Tribe’s goals and objectives.

The location of the community solar project also makes a difference. A project in a sunny region with high electricity costs might see a higher ROI (closer to 20%). Conversely, a less sunny area with lower electricity rates might have a lower ROI (closer to 10%). Overall, community solar offers financial benefits through electricity cost savings and generates profit, but the specific ROI will depend on your location and project details.

-

Yes, Tribes can now take advantage of federal solar tax credits thanks to the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022. Previously, their tax-exempt status prevented them from directly claiming these credits. The options include:

Direct Pay Option: The IRA introduced a "direct pay" option for Tribes. This allows them to receive a cash payment from the IRS equivalent to the amount of the tax credit they would have otherwise received.

Increased Accessibility: The IRA also expanded the two main solar tax credits, the Investment Tax Credit (ITC) and the Production Tax Credit (PTC), making them more accessible to Tribes. These credits can significantly reduce the upfront costs of installing solar panels.

Bonus Credits: Tribes may also be eligible for additional bonus credits depending on factors like project location and community served.

Development Process & Other Considerations

-

Tribes have a couple of options to receive technical assistance for assessing a community solar project's viability:

Department of Energy's START Program: The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Indian Energy offers the Strategic Technical Assistance Response Team (START) program. This program provides on-site technical expertise from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) to federally recognized Tribes for renewable energy projects, including community solar.

Tribal Energy Organizations: Several Tribal energy organizations offer technical assistance programs specifically focused on renewable energy development on Tribal lands. These organizations can help Tribes assess technical feasibility, conduct feasibility studies, and navigate permitting processes

-

The community solar program ensures that projects receive compensation for the energy they generate over a 25-year period. While the warranty lifespan of projects commonly aligns with this duration, it may vary based on manufacturer specifications and performance warranties provided by solar installers. Beyond the initial 25 to 30 years, solar panels may experience a gradual decline in power output. Nevertheless, diligent maintenance practices can enable projects to sustain power generation for up to 40 years.

-

The operations and maintenance (O&M) of a community solar project are crucial for ensuring it delivers its maximum benefits over its lifespan. Here's a breakdown of the key aspects:

Goals of O&M:

Optimize Performance: Regular maintenance keeps the solar panels and system components functioning efficiently, maximizing electricity generation.

Preventative Measures: Proactive inspections and cleaning identify and address potential issues early on, preventing major breakdowns and costly repairs.

System Longevity: Proper care extends the lifespan of the solar panels and equipment, ensuring the project delivers clean energy for a longer period.

Safety: O&M procedures prioritize safety by checking for electrical hazards, loose connections, and potential fire risks.

Key O&M Activities:

System Monitoring: Continuous monitoring tracks the system's performance, power output, and identifies any deviations from expected levels.

Regular Inspections: Scheduled inspections involve visual checks of the panels, electrical connections, mounting systems, and surrounding vegetation for damage, debris, or shading issues.

Cleaning: Periodic cleaning removes dust, dirt, and bird droppings that can reduce the efficiency of the solar panels.

Preventative Maintenance: Based on the inspection findings, maintenance tasks like tightening loose connections, replacing worn-out parts, and inverter servicing are performed.

Record Keeping: Detailed records of inspections, maintenance performed, and system performance are maintained for future reference and troubleshooting.

Who Handles O&M?

There are two main approaches:

Internal O&M Team: The community solar project might have a dedicated in-house team with the technical expertise to handle O&M tasks.

Contracted O&M Services: The project can contract with a specialized O&M service provider who takes care of all maintenance needs.

Additional Considerations:

Drone Technology: Some O&M providers utilize drones with thermal imaging cameras to conduct inspections, improving efficiency and safety.

Data Analytics: Advanced data analysis of system performance can help predict potential issues and optimize maintenance scheduling.

By implementing a comprehensive O&M plan, a community solar project can guarantee it delivers clean energy efficiently and reliably throughout its operational life.

-

After a community solar project reaches the end of its operational life, the land undergoes a process called decommissioning. Here's what happens to the land during this stage:

Equipment Removal: Solar panels, mounting structures, electrical wiring, and inverters are carefully dismantled and removed from the site.

Land Restoration: The land is then prepped for its return to its original state or another designated use. This may involve:

Soil de-compaction: The soil that was potentially compacted during construction is loosened to improve drainage and air circulation.

Backfilling: Any trenches dug for electrical lines or mounting systems are filled back in.

Revegetation: Native plants and grasses are reintroduced to the site to restore the original ecosystem or establish a new one if desired.

Decommissioning Plan: The decommissioning process typically follows a plan that's established during the initial project proposal stage. This plan ensures the land is restored responsibly and in accordance with environmental regulations.

Here are some additional points to consider:

Land Use After Decommissioning: The land can be returned to its original use, such as agriculture or grazing, or converted to another purpose, like a community garden or recreational area, depending on the plan and community needs.

Sustainability Efforts: Decommissioning can be done sustainably by recycling or repurposing some of the removed materials, like the aluminum frames of the solar panels.

Landowner Responsibilities: The decommissioning process is usually the responsibility of the solar project owner, which could be the community solar developer or the Tribe itself, depending on the ownership model.

Overall, the goal of decommissioning is to ensure the land used for the community solar project returns to a productive and ecologically sound state after the project's lifespan

-

Battery energy storage systems can be added to community solar arrays to provide electricity when the sun isn’t shining. Combining solar and storage can increase resilience by providing backup power during an electrical disruption.